|

|

MusicSega Master System / Mark III / Game Gear |

Home - Forums - Games - Scans - Maps - Cheats - Credits |

Music Engine Triggers

Introduction

On the Master System, many games' music engines work by having the music engine check one or more memory locations once per frame for some commands sent by the main game engine. Commands will be things like

- play music track 3

- play sound effect 14

- pause

- fade out

If we can find these memory locations then we can take control of the music engine and make it play any sound we want, including some that aren't played in the game (secret music) and some that are cut off by the game.

This guide explains how to easily find these hacks by exploiting common characteristics of Master System (and Game Gear) music engines.

The method

My experience has shown me a few things:

- Music engines are usually fairly independent from the rest of the game

- The game code thus usually controls the music engine using a single-byte variable in RAM

- This control variable is usually close to the other RAM used by the music engine

- This RAM variable's value is very often (but not always) something like $81 - ie. a small number with the high bit set.

Modern advanced emulators include one very useful feature: memory viewers/editors. These allow me to see what's in memory and to change it while the game is running. I'm going to use this to make a music hack.

The guide

Open the game in the emulator

In this example, I'm using Alex Kidd in Shinobi World. You can follow along with the same game.

Open the RAM viewer

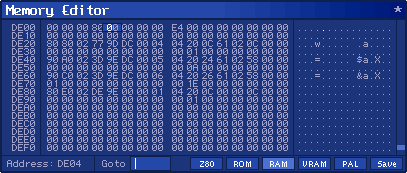

I'm using Meka, but Emukon is just as good. To open it in Meka, click on TOOLS - Memory Editor. Then click on the 'RAM' button to jump to the start of RAM.

As the game plays, you should see the values changing.

Look for the music engine's RAM

Scroll through the RAM while the intro runs, and music is playing. You are looking for the music engine's RAM. The way to recognise this is to notice that music RAM changes very quickly and tends to all be in a relatively small block (less than 512 bytes). This is because music is complicated - the engine has to handle effects like vibrato, volume envelopes and fading on three channels at once, and music changes notes many times each second - and, as noted above, generally independently developed so it has to keep to a small area of RAM to avoid clashing with the rest of the game.

It is also easy to recognise because it should be changing exactly in time with every change in the music.

Scroll a page at a time through the RAM, either using the mouse wheel or the Page Up/Page Down keys. (You might need to set Meka to 1/1 frameskip to make it notice your keypresses properly.) If the game demo starts, a lot more RAM will be actively used by the game engine. Just reset the game when this happens (the Backspace key) and wait for the music to start before resuming the search.

You should eventually find it at about offset $de00.

Find the trigger point by watching as the music changes

Now comes the detailed searching. Make the game run until just before a point where it changes the music. Save the game state (the F5 key) about a second before it changes. Then look closely at the music RAM.

Load the game state (the F7 key) and look closely; you're looking for one of the following:

- A value that is constant before the music changes, then changes at the same time as the music, and is then constant, or

- A value that is constant (often $00 or $80) before the music changes, then has a value for one frame only, at the moment the music changes; it then goes back to "nothing"

You should definitely set the frameskip to 1/1 to be sure of being able to see the second one; alternatively, a slow emulated speed such as 20Hz makes it easier to spot. In our case, it's not too hard; I can see that offset $DE04, just 4 bytes in, seems to be acting as described in the second case above. This isn't surprising - it makes sense for the control variable to be near the start, since it would be one of the first things written in the music engine.

Click on it so that it is highlighted and the address of that byte will be displayed in the lower-left corner. Make a note of it, so you can tell us about it once you've finished.

Write into it

Next, we are going to write a new value to this address. The value I will write is $81. This is often a good value to try. While the correct address is selected, enter a new value for the byte by typing in the two hexadecimal digits (8 and 1). (Again, you may need to set Meka to 1/1 frameskip to be able to type.) After you type the second digit, the value is written and the highlight moves to the next byte. You will also notice that

- The value we just wrote is changed to zero by the game

- The music changes to the Level 1 tune

This shows that we have found our variable :) This address is a write trigger - writing a new value there causes the music to change. This is the easiest kind of music hack because it doesn't require us to even look at the code!

Making it easier to rip the VGMs

When ripping VGMs, it's better to log the music with silence at the start (it makes trimming easier) and with no sound effects playing over it (since they ruin the music).

To make silence at the start, try writing different values to the music control variable. Ones to try include:

- $80 - some games use index 0 for silence

- $00 - it is easy to test for in Z80 code

- $ff - another "nothing" value

- Finally, see if there is a short piece of music that does not loop - perhaps a "level start" or "death" sound. You can play it to stop the current track, and when it finishes you have silence.

For Alex Kidd in Shinobi World, writing $ff works well.

To avoid sound effects we have several options. First, we can use the pause button hack. A second choice is to play the game a bit and find somewhere where sound effects do not happen, and the music does not change. Try when the game is paused, or an options screen. Even if they don't have music, the music engine may still be active - try writing a value as described above in these situations and see what happens.

For Alex Kidd in Shinobi World, the Pause hack works well. With both, you are able to change the music while it is playing, so there is no need to exit the emulator, edit files, load and save states or reset the game each time you want to rip a different track.

Conclusion

We can go through all of the possible values for the music engine, write them at $DE04, and they will play. We can then list what each value does and rip the music. In most music engines, the lower numbers are music; the higher ones are sound effects, and too-high values will either produce silence, random sounds or crash the game. It's always worth checking more possible values, though: there may be some music tracks mixed in with the sound effects, and there may be some invalid values mixed in with the valid ones.

Write down the results because they might be useful in case you need to re-rip the music. Here are the Alex Kidd in Shinobi World sound engine values:

| $80 | No effect |

| $81 | Level 1 |

| $82 | Level 2 |

| $83 | Level 3 |

| $84 | Level 4 |

| $85 | Level Start |

| $86 | Death |

| $87 | Boss Music |

| $88 | Level Complete |

| $89 | Unused music |

| $8a | Continue Screen |

| $8b | Unused music (short) |

| $8c | Unused music (short) |

| $8d | Congratulations To You, Alex |

| $8e | Intro |

| $8f | Unused music |

| $90-$b4 | Sound effects |

| $b5-$b6 | Silent |

| $b7+ | Errors |

Other Music Engines

There are lots of different ways for music engines to work. This guide only covers one of them. It is the most common type, especially in first-party Sega titles, so it should set you on your way to hacking games yourself.

The main alternatives are:

- Games where the music control variable is somewhere totally different to the music engine. You can hack these by (tediously) searching the whole of RAM for the variable, instead of focusing just on the music engine's RAM area.

- Games which require a function call in the code to change the music, but still use a memory location to select the music. These won't respond when the byte is written; they have to be hacked.

- Games which require a function call in the code to change the music, and pass the parameter in a register. These are more tricky because there isn't an address to search for in the disassembly. Finding the music engine's entry point helps with these, since you can find calls to it or even hack it directly.

- Games which use non-sequential music numbers. Several games with music code written by Matt Furniss, for example, use "blocks" of music; a short track might take 1, a long one might take 5. Their music numbers are references to blocks, so the numbers might be 1, 2, 3, 8, 13, and trying block number 5 would give you music part-way through a track and possibly with some errors.

- Games where the music control variable passes through a chain of other code before being written. You may have to try to trace the execution backwards to find out how to control the music engine.

There is also the problem of avoiding music interruptions on non-SMS games, and games where the pause hack doesn't work. This is all rather complicated so I'll not go into it too deeply; but note that the memory editor lets you find lots of things, including title screen timeout timers ($ffff frames is plenty of time for most tracks), in-game timers, invincibility flags, etc.

I used Meka in this guide because it's pretty and its memory editor does everything I need. Other emulators may offer the features needed; Emukon is very good for debugging and hacking, but it runs slowly on my computer.

If you want to distribute your ROM or RAM hacks to others, it is sometimes better (if possible - it is not with "write trigger" hacks) to create patch file entries because they may be easier to apply. See the emulator's documentation for instructions; Meka's meka.pat file is self-documenting.

The best thing you can do with any successful hacking is to tell other people. Post it in the Hacks to find music forum thread, and everyone will love you just a little bit more.

Why is $81 a good value to try?

In my experience, the majority of games' music engines work using control values where the high bit is set. This means that the values passed to the music engine are simple numbers selecting the music from a list (1, 2, 3, ...) but the numbers have their high bit set, so they become ($81, $82, $83, ...). The music engine does a first check on the value by checking if the high bit is set. If it isn't, it rejects it. It then resets the high bit and uses the value as an index into a lookup table to find the music data, and begins playing.

I can't think of a good explanation for this, but it is generally true, especially for games made by Sega. Since $80 is often used for silence, $81 is generally the starting value. When hacking a music engine, pay attention to the parameters being used by the game; if it is always using values like $8x and $9x then you've got a high-bit engine; if it's using $0x and $1x then obviously you haven't. (Try slowing down emulation, and/or using the emulator's "run for 1 frame" option (Alt+F12 in Meka), to spy on values being written to a particular address.)

When you're writing values, note that if the currently playing music is number $81, writing $81 might not change anything. So if nothing happens when you expected it to, try $82.